Uniswap V2 Mint and Burn Functions Explained

The lifecycle of Uniswap V2 is someone mints LP tokens (supplies liquidity, i.e. tokens to the pool) for the first time, then a second depositor mints liquidity, swaps happen, then eventually the liquidity providers burn their LP tokens to redeem pool tokens.

It turns out to be easier to study these functions in reverse – burning, minting liquidity, then minting the initial liquidity.

So let’s begin with burn.

Uniswap V2 Burn

Before liquidity tokens can be burned, there needs to be liquidity in the pool, so let’s make that assumption. We assume that there are two tokens in the system: token0 and token1.

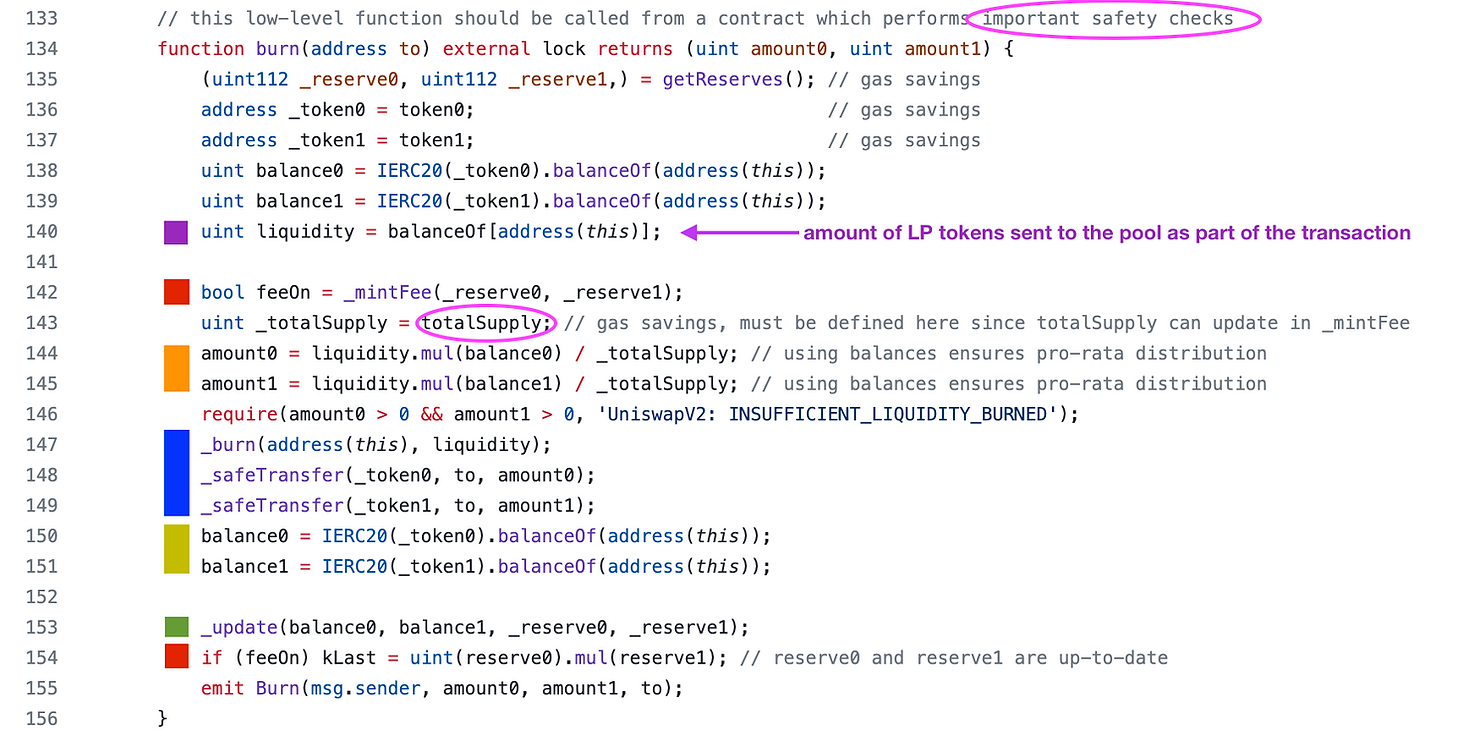

We’ve annotated the burn function below, we will explain the parts that aren’t totally obvious.

On line 140 (purple box), liquidity is measured by the amount of LP tokens owned by the pool contract. It is assumed that the burner sent in LP tokens before calling burn, but advisably as part of one transaction. (If they are sent as two transactions, someone else can burn your LP tokens and remove your liquidity!) The amount the user sent to the contract will be burned. In general, we can assume that the contract will have a zero balance of LP tokens, because if LP tokens are just sitting in the pair contract, someone will burn them and claim some of the token0 and token1 for free. The mechanism of sending tokens as part of the transaction was introduced in the article on Uniswap V2 Swap.

The red boxes on lines 142 and 154 denote fees, we will skip those for now as Uniswap does not apply fees to liquidity providers.

The orange boxes on lines 144 to 145 are where the amounts that the LP provider will get back are calculated. If the total supply of liquidity tokens is 1,000, and they burn 100 LP tokens, then they get 10% of the token0 and token1 held by the pool. Liquidity / totalSupply is their burned share of the total supply of LP tokens.

The blue box on line 147 to 149 is where the LP tokens are actually burned and the token0 and token1 are sent to the liquidity provider.

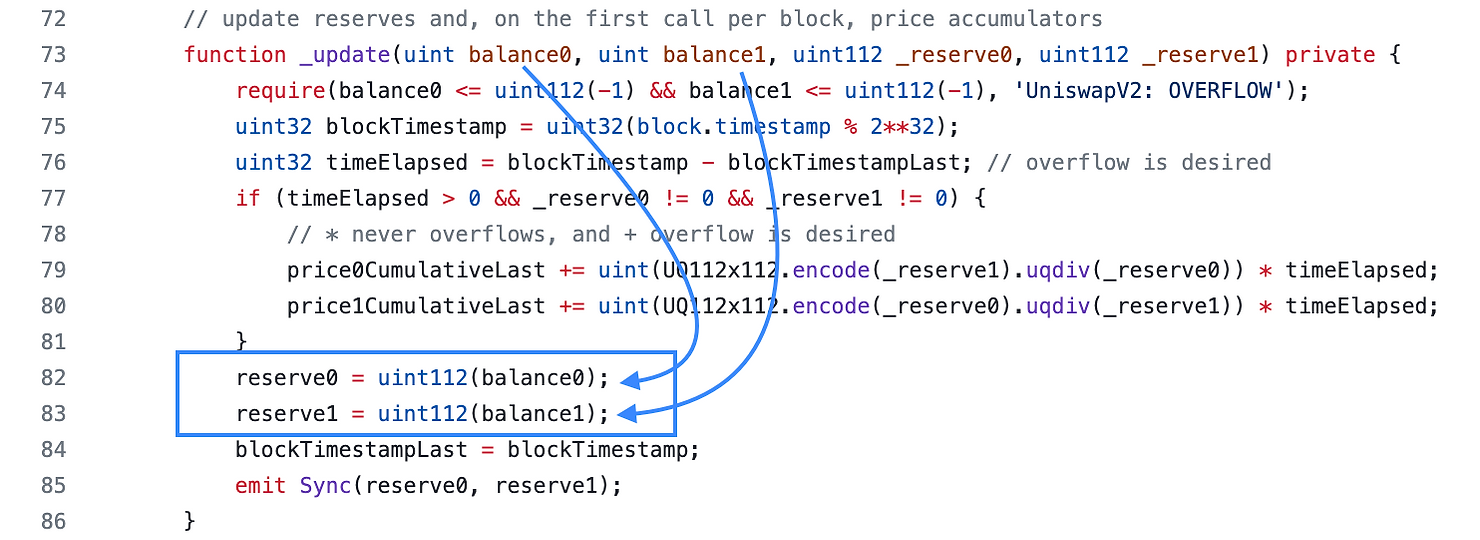

The yellow box on lines 150-151 updates the balance variables so that the call to _update on line 153(green box) can update the _reserve variables. Aside from updating the TWAP, the _update function simply updates the _reserve variables.

Safety Checks

Suppose the pool has equivalent amounts of token0 and token1. This means the burner expects to receive both tokens in equal quantity when burning the LP token. However, the pool ratio of token0 to token1 can change between when the burn transaction is signed and when it is confirmed. If the burner has downstream logic that depends on receiving a particular amount of token0 or token1 (such as paying back a flash loan), then that logic could break if it receives slightly less token0 or token1. The burning contract must be prepared to receive less token0 or token1 than expected and revert if needed.

Minting liquidity when the pool is not empty

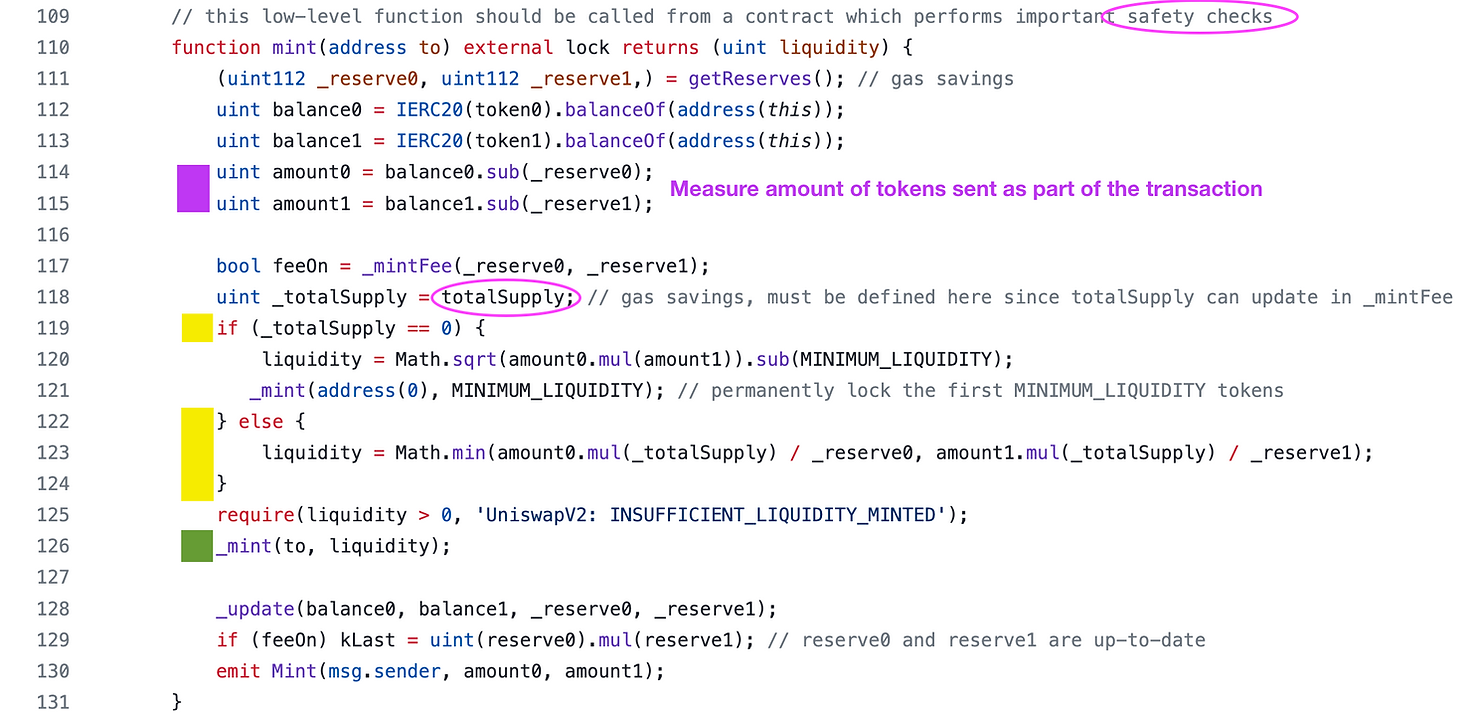

Here is the mint liquidity function. Much of the functionality is similar to burn, so we will not repeat the parts that should be obvious.

If the pool is empty, that is, liquidity tokens have a total supply of zero, then no liquidity has been provided yet. This is checked on line 119 (The yellow box). In this section, we focus on the case where liquidity has already been provided (yellow box on line 123). The liquidity that is credited to the user, and later minted to them on line 126 (green box), is the lesser of two values.

The ratio that this line of code is measuring is amount0 / _reserve0 – scaled by the totalSupply of LP tokens.

Let’s say there are 10 token0 and 10 token1. If the user supplied 10 token0 and 0 token1, they will get the minimum of (10/10, 0/10) and get zero liquidity tokens back! Another example: if they increase the supply of LP tokens (remember, this ratio is scaled by _totalSupply which is the current supply of LP tokens).

The fact that the user will get the worse of the two ratios (amount0 / _reserve0 or amount1 / _reserve1) that they provide, incentivizes them to increase the supply of token0 and token1 without changing the ration of token0 and token1.

Why enforce this? Let’s say the pool currently has 100 of token0 and 1 of token1, and the supply of LP tokens is 1. Let’s say the total value, in dollars, of both tokens is \$100 each, so the total value of the pool is \$200.

If we took the maximum of the two ratios, someone could supply one additional token1 (at a cost of \$100) and raise the pool value to $300. They’ve increased the pool value by 50%. However, under the maximum calculation, they would get minted 1 LP token, meaning they own 50% of the supply of LP tokens, since the total circulating supply is now 2 LP tokens. Now they control 50% of the \$300 pool (worth \$150) by depositing only \$100 of value. This is clearly stealing from other LP providers.

Supply Ratio Safety Check

The user might try to respect the token ratios, but if another transaction executes in front of them and changes the balance of token0 to token1, then they will get fewer liquidity tokens back than they expected.

Uniswap doesn’t require exact amounts because otherwise the transaction would likely revert. Another transaction executed first would change the requirement between when the minter sent the transaction and when it was included in the block.

TotalSupply Safety Check

Just like the burn case, the totalSupply of LP tokens could change at the time, so some slippage protection must be implemented.

The First Minter Problem

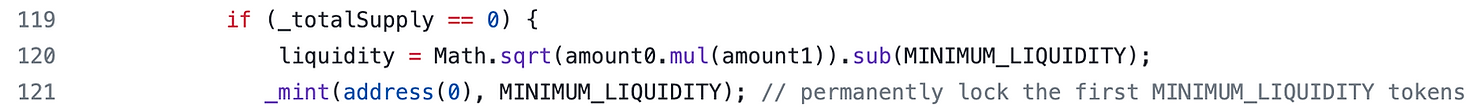

Like any LP pool, Uniswap V2 needs defense against the "inflation attack." We’ve described this problem, and defense against it, in our article on ERC4626, so we won’t repeat it here. Uniswap V2’s defense is to burn first MINIMUM_LIQUIDITY tokens to ensure no-one owns the entire supply of LP tokens and can easily manipulate the price. Again, please refer to the other article if you are unfamiliar with this attack vector.

Why Uniswap Calculates Liquidity as Square Root K

The more interesting question is why Uniswap V2 takes the square root of the product of the tokens supplied to calculate the amount of LP shares to mint.

Specifically, liquidity = sqrt(amount0*amount) after subtracting the MINIMUM_LIQUIDITY.

It would seem that we could mint an arbitrary amount of tokens to the first LP – they own 100% of the shares (minus what was burned), so what difference does it make if it is scaled by 0.01 or 100?

Here is the whitepaper’s justification:

Uniswap v2 initially mints shares equal to the geometric mean of the amounts, liquidity = sqrt(xy). This formula ensures that the value of a liquidity pool share at any time is essentially independent of the ratio at which liquidity was initially deposited… The above formula ensures that a liquidity pool share will never be worth less than the geometric mean of the reserves in that pool.

What exactly is meant by that?

One of the best ways to get an intuition for something is to plug in values and see what happens, so let’s do that.

Example: Doubling Liquidity

Let’s suppose we didn’t measure liquidity with the square root function and we start with 10 of token0 and 10 token1 in the pool. Later on, the pool has 20 of token0 and 20 of token1 in the pool.

Intuitively, did the liquidity double or quadruple? Because if we don’t take the square root, liquidity would start at 100 (10×10) and end up at 400 (20×20). Arguably, liquidity did not quadruple. At first, the maximum of token0 you could obtain was (asymptotically) at 100, but after growth in liquidity, the "depth" of the liquidity for that token doubled, not quadrupled.

But how does this matter if future liquidity providers are not calculating liquidity using the square root while minting or burning? We saw new liquidity providers are "forced" to supply assets at the current rate, and burners can only redeem at the current rate – no square roots are involved.

The answer lies in how Uniswap would have collected fees from LPs if it chose to do so.

Fees

Going back to our earlier example of the pool growing from 100 of token0 and 100 of token1, to 200 of each, the profit of the liquidity provider is 100%, so they should pay a fee proportional to that amount. If we measured the size of the pool from 100 to 400, then they would have to pay fees on quadruple profit.

Uniswap opts to charge fees during liquidity removal because charging a protocol fee during swapping would increase the gas cost of a very common operation. Uniswap V2 never actually turned on the protocol fee, so this discussion is a bit theoretical.

Originally Published Oct 30, 2023